Scans that show snippets are legal—they don't replace the full book.

A long-running copyright lawsuit between the Authors' Guild and Google over its book-scanning project is over, and Google has won on the grounds that its scanning is "fair use."

In other words, the snippets of books that Google shows for free don't break copyright, and Google doesn't need the authors' permission to engage in the scanning and display of short bits of books.

In other words, the snippets of books that Google shows for free don't break copyright, and Google doesn't need the authors' permission to engage in the scanning and display of short bits of books.The ruling (PDF) was published this morning by US District Judge Denny Chin, who has overseen the case since it was filed in 2005.

The parties tried to settle this case, but the judge rejected the settlement as unwieldy and unfair. Now, the case has instead resulted in a hugely significant fair use win, opening the door to other large-scale scanning projects in the future.

Along with the First Sale doctrine, fair use is the most important limitation on copyright. It allows parts of works to be used without permission of the copyright owner to produce new things: quotes of books used in reviews or articles for instance.

Legal disputes over what or what is not "fair use" are often complex, and there are four factors that judges consider. But the one that's often the most important is what kind of effect the fair use will have on the market for the original product.

Judge Chin seemed to find the plaintiffs' ideas ignorant, if not nonsensical, in this regard. He wrote:

[P]laintiffs argue that Google Books will negatively impact the market for books and that Google's scans will serve as a "market replacement" for books. [The complaint] also argues that users could put in multiple searches, varying slightly the search terms, to access an entire book.

Neither suggestion makes sense. Google does not sell its scans, and the scans do not replace the books. While partner libraries have the ability to download a scan of a book from their collections, they owned the books already—they provided the original book to Google to scan. Nor is it likely that someone would take the time and energy to input countless searches to try and get enough snippets to comprise an entire book.

Seeing the project as a boon to researchers

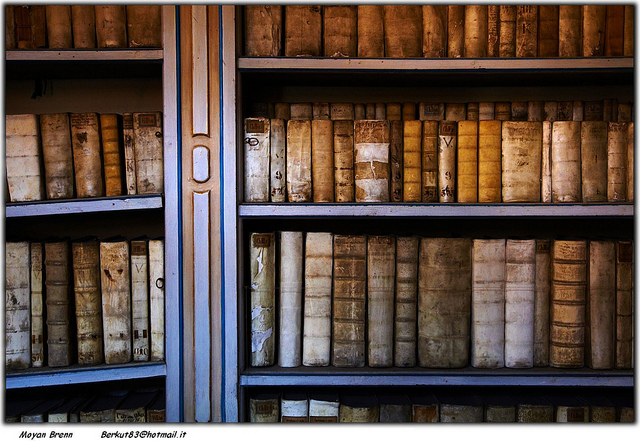

Before Chin gets into the deep legal analysis, he begins with a section noting the many benefits of Google books. The giant book-scanning project has already become an "important tool for researchers and librarians," noted Chin. Through data mining, researchers can do things they've never been able to do before, examining "word frequencies, syntactic patterns, and thematic markers to consider how literary style has changed over time."The program expands access to books, particularly to "traditionally underserved populations," he notes. The books Google scans provide the potential for them to be read in larger text formats or with Braille or text-to-speech software. And the project could save old out-of-print books that are literally falling apart in library stacks.

Chin runs through the four traditional factors that decide whether use of a copyrighted work is "fair use."

First, he found Google's use of the works was highly transformative. "Google Books digitizes books and transforms expressive text into a comprehensive word index," he wrote. There's already legal precedent allowing large-scale scanning in order to create indexes and search services—created, in part, by Google. Chin cited the Perfect 10 v. Amazon case, which ruled the scanning of images and publication of "thumbnails" in Google image search is legal.

He also found that Google Books "does not supersede or supplant books because it is not a tool to be used to read books." The service adds value to books.

Chin notes that Google is a commercial service, which weighs against a finding of fair use. But while the service may draw more people to Google websites, Google isn't engaged in "direct commercialization" of the copyrighted works. The company "does not sell the scans it has made of books for Google Books; it does not sell the snippets that it displays; and it does not run ads on the About the Book pages that contain snippets."

Another factor is the amount of the work used. Google is scanning full books. But "copying the entirety of a work is sometimes necessary to make a fair use of the image," wrote Chin, citing a case involving the use of reduced-sized Grateful Dead posters called Bill Graham Archives v. Dorling Kindersley.

Important, of course, is the fact that Google is showing limited amounts of text to book searchers. Blacked-out sections and other technical measures prevent full-book copying.

In the end, the full-book scanning weighed only "slightly against" a finding of fair use. It was overridden by the other factors. Especially important was Chin's view, discussed above, that Google Books would not hurt, and may in fact help, the market for the original books.

A nearly-settled case will now be fought on appeal

The parties tried to settle this case but were unable to. A proposed settlement not only involved a complicated set of compensation rules for authors, it also had sections dealing with unaddressed copyright issues like "orphan works." But Chin rejected the settlement in 2011, saying it wasn't fair. Fundamentally, it was just too big—issues like orphan works were best left to Congress, not to a class-action lawsuit.

In the long term, the failure to settle may result in more scanning, not less. If Chin's ruling stands on appeal, a clean fair-use ruling will make it easier for competitors to start businesses or projects based on scanning books—including companies that don't have the resources, legal or otherwise, that Google has.

"This has been a long road and we are absolutely delighted with today’s judgment," said a Google spokesperson. "As we have long said., Google Books is in compliance with copyright law and acts like a card catalog for the digital age, giving users the ability to find books to buy or borrow."

Authors' Guild Executive Director Paul Aiken expressed his disappointment with the ruling, saying that Google's book-scanning project is a "fundamental challenge" to copyright.

"Google made unauthorized digital editions of nearly all of the world's valuable copyright-protected literature and profits from displaying those works," said Aiken. "In our view, such mass digitization and exploitation far exceeds the bounds of the fair use defense."

The Guild is going to appeal, he added.

That means the issue will end up at the New York-based US Court of Appeal for the 2nd Circuit. That appeals court has decided several key legal battles between content and technology companies in recent years, including the Cablevision decision. That ruling legalized remote-DVR services, which has aided other tech companies, including Aereo.

Fundamentally, the fact that this case was finally decided on its merits, and not settled, is a better result for the public, argued Paul Alan Levy of Public Citizen in his reaction this morning.

"Unlike that settlement, which could have ensconced Google as the only search engine entitled to digitize books without the consent of their authors, this ruling provides a road map that allows any other entity to follow in Google’s path," said Levy.

It's judges' decisions in hard-fought cases—not overseeing secret negotiations between giants—that truly benefit the public.

"[T]he main job of a federal judge is not to supervise settlements, and especially not to bully parties into settling their cases," he wrote. "The judge’s job is to decide cases, so that every member of the public, not only the parties, can benefit from the public resources that go into the judicial system."

Πηγή: arstechnica.com

.jpg)

.jpg)

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου